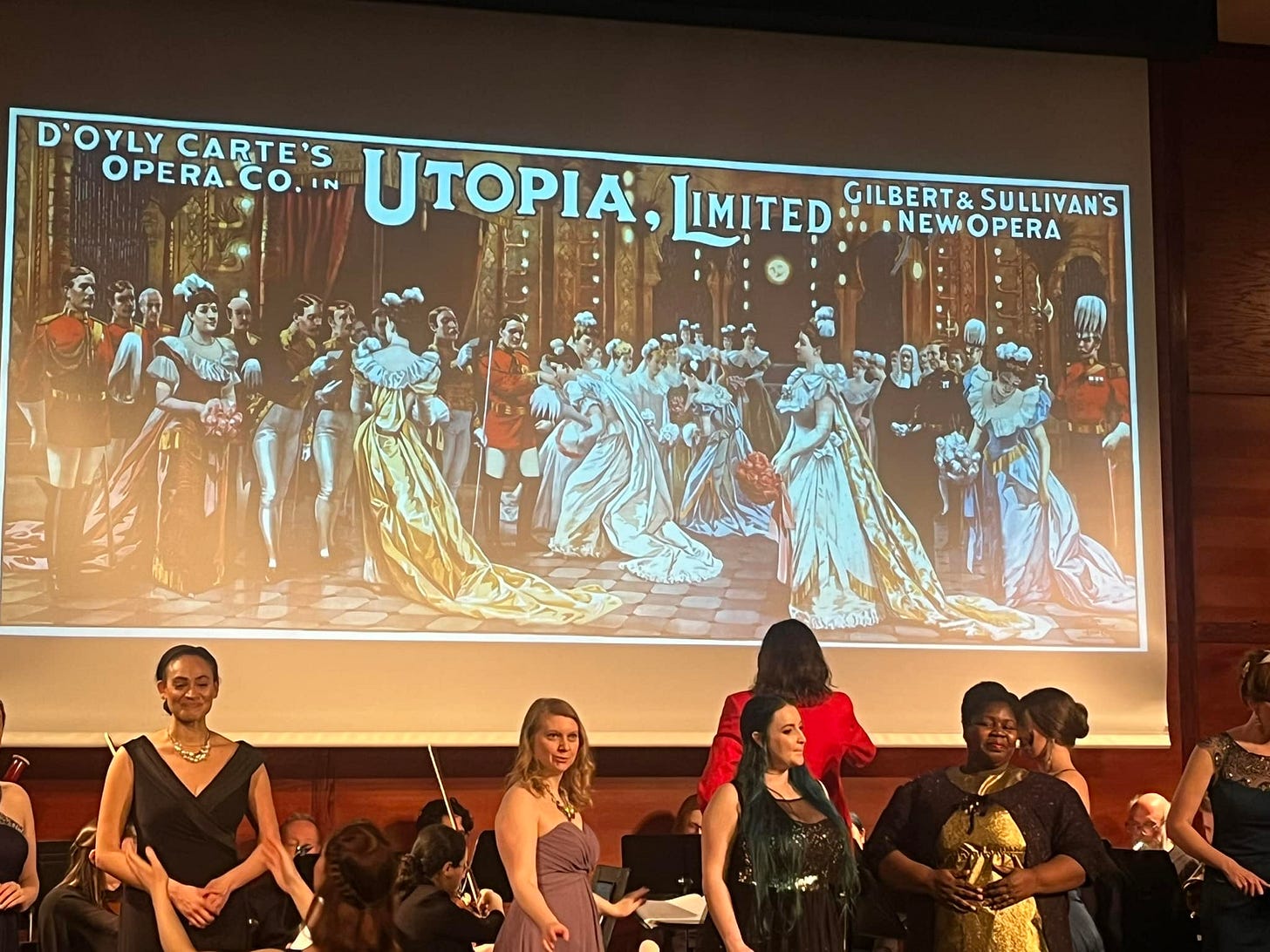

This weekend something astonishing happened. Utopia Opera, a company that seeks to bring creatively performed opera to the masses, founded by William Remmers in 2011, performed a semi-staged production of Utopia, Limited. Utopia, Limited gives the opera company its name and is the title of Gilbert and Sullivan’s penultimate work, which premiered at their Savoy Theatre on October 7, 1893.

For a The Ultimate Millennial Gilbert and Sullivan Superfan (that’s me), and for any G&S obsessive, seeing Utopia in person is a real treat. Why? Because it’s so rarely performed. It’s easy to find Penzance or Pinafore around Christmas or in summer if you live near a major East Coast city, and if you’re like me, you happily go to as many Penzances and Pinafores as you can, but Utopia almost never happens, and most normal humans have never heard of it.

This is because it was made in the twilight of Gilbert and Sullivan’s career, after their infamous Carpet Quarrel of 1890 when Gilbert sued Sullivan and their impresario D’Oyly Carte supposedly over having to pay exorbitant prices for the carpets that decorated their theater during the run of 1889’s The Gondoliers. (The Gondoliers is a very cute, sunny and bright operetta that I finally got to see live last fall! I also listened to it while getting a root canal at the height of the pandemic because its long and happy score, as well as substantial novocaine, helped me get through the procedure.) Even though carpets infamously started this quarrel, they weren’t really the point: Gilbert basically felt unseen and unappreciated by his collaborators after decades of tensions, was concerned that D’Oyly Carte was swindling him, and he expressed himself litigiously.

Once G&S made up after the quarrel, they were hesitant to be honest with each other and edit each other’s works. They were on tenterhooks with one another. So the 1890s operettas, Utopia, Limited and The Grand Duke, are overstuffed, with too many characters, words, unresolved plot lines and some repetitive, less imaginative music (though not exclusively). This means they can be tedious to watch and expensive to put on, and so they’re rarely done.

However, they can be well done, and Utopia Opera proved that. Even I, G&S obsessive that I am, was worried that I would get bored, with a ninety minute first act and sixty minute second act. But the performance felt breezy and delightful! This is due to the incredible expertise, wit and humor of the whole company, from Remmers’ direction and dandyesque performance of King Paramount, to all of the actor-singers and to the wonderful orchestra musicians. Everyone and everything was incredible. In a small environment like Hunter College’s Ida K. Lang Recital Hall, it’s easy for a full orchestra to drown out the singers, but that didn’t happen at all, first because the singers were so accomplished, and second because Utopia has so many characters and so many of them would sing at once!

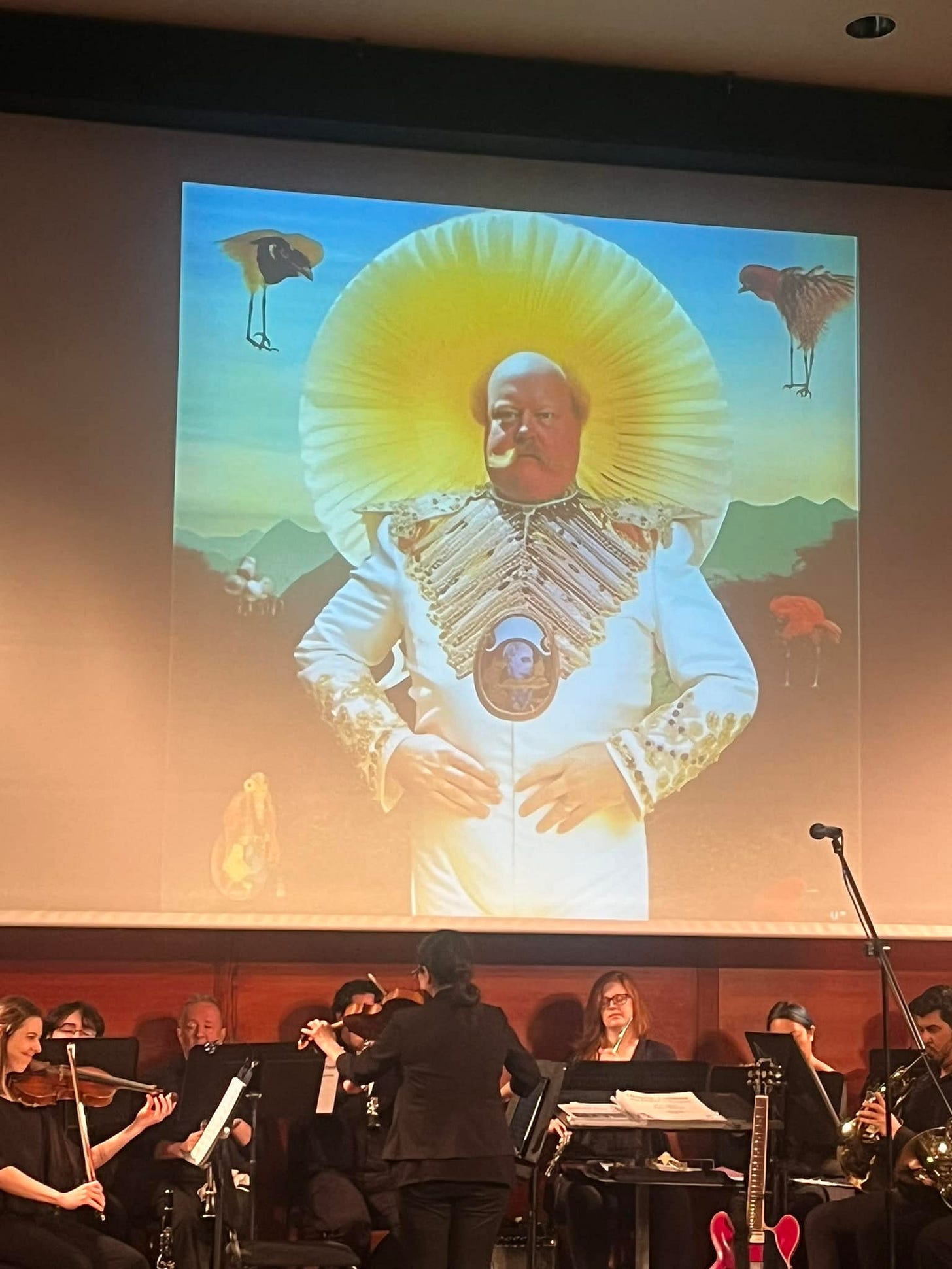

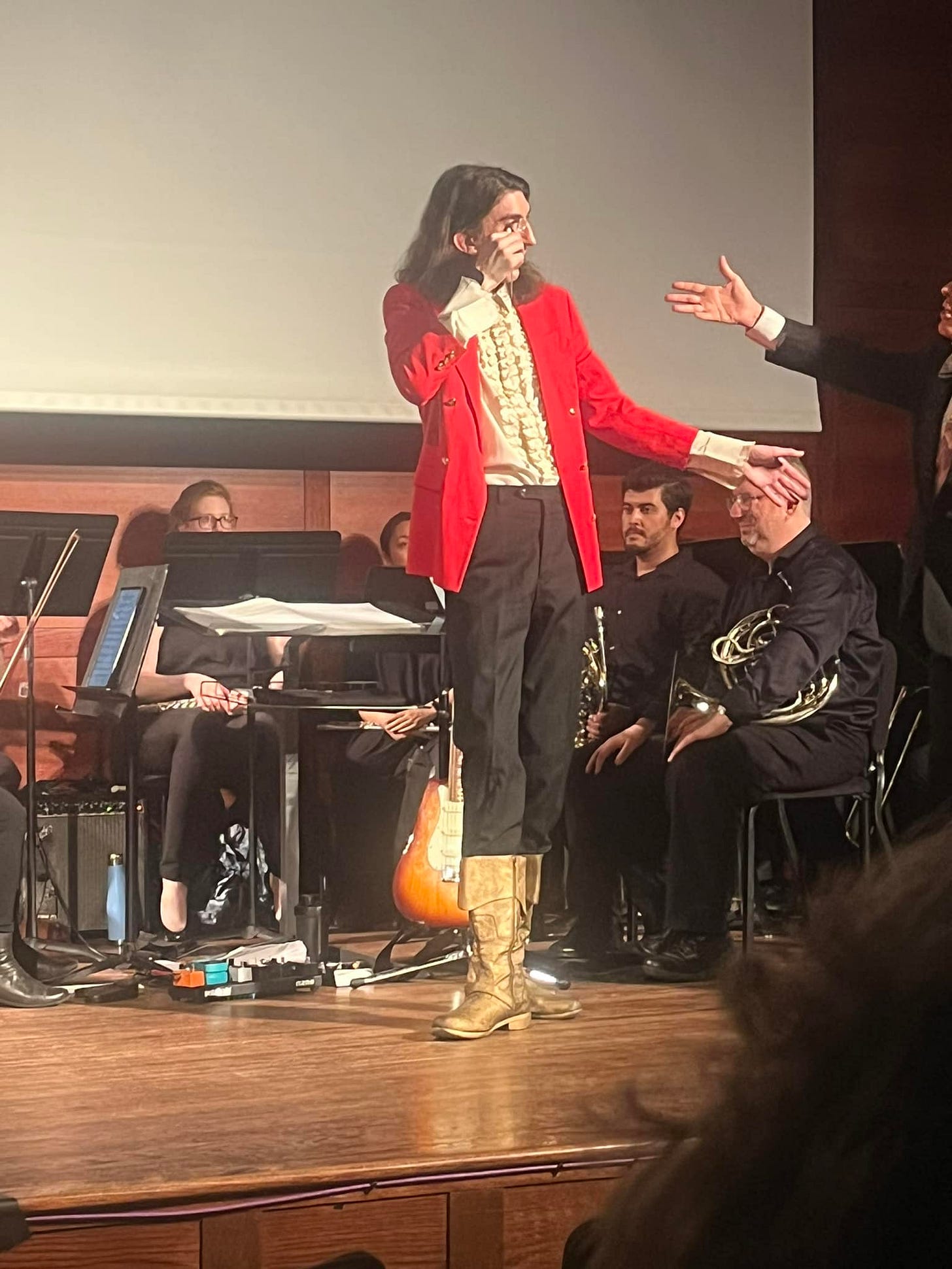

Remmers brought an imaginative Beatles theme to the performance. In fact, he led a singalong at the beginning to Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band while playing electric guitar. I’m not entirely sure why this was done, but, as with all things Utopia Opera, there is a certain cleverness in it: just as Gilbert and Sullivan were the most popular English import to the United States in the late nineteenth century, The Beatles stormed American shores in the mid to late twentieth. I also think the company simply likes The Beatles and wanted to be entertaining. My liking of The Beatles is mild — I’m more of a Simon and Garfunkel person. It still showed Utopia Opera’s admirable commitment to creativity, fun, and making somewhat arcane late Gilbert and Sullivan relatable to a modern audience of all ages. It, along with some imaginative AI art projected onto the screen, gave everything a psychedelic cast, and, in fact, the citizens of Utopia wore tie dye, paisley, and vaguely hallucinatory patterns.

Despite some of these more contemporary choices, Gilbert and Sullivan themselves were very present. Parts of the libretto were cut, but the distinctive songs, lyrics, and dialogue of Utopia, Limited were all there, and they were nice and speedy. This might be a controversial aspect of the show, but to me it was enormously successful: the tempi were very, very fast. This made everything go at a brisk pace and not be tedious. It heightened the humor; everything was a bit burlesque like a rushed silent movie. But instead of being silent, the playful, tongue twisting nature of Gilbert’s clever and convoluted lyrics was enhanced as the singers had to “patter through it” as quickly as possible. I think it was a very smart choice for an operetta that can easily drag on.

It also helped that there was a large screen that would project the words to the songs. This is a common practice in opera, especially for non-English operas so English-speaking viewers can understand, but I have not seen it done for Gilbert and Sullivan until now. It’s yet another intelligent choice. It’s easier to connect to the opera when you can follow along with the words and see their cleverness. In the 1870s and 1880s, when most Gilbert and Sullivan operettas premiered, it was common practice for theaters to keep their lights on so people could read their libretti (the words) during the show. This is a practice we should bring back in as many ways as possible.

The acting and singing was top notch across the board. As Phylla, Ali Roselle brought her stunning, agile voice to the soaring soprano solos during the opening chorus, “In Lazy Languor Motionless.” She took a wonderfully cult-like approach to her character, looking straight at the audience with an almost alien zeal as she proclaimed that Utopia would now be modeled on English customs. This unusual delivery of lines, probably inspired at least in part by Remmers, made the audience laugh at both performances. Angela Scorese as Salata and Devyn White as Melene rounded out the trio of head Utopian maidens; they brought freshness and delight to their roles.

The cult theme Utopia Opera emphasized in this show was inspired and deeply effective, underscoring Utopia, Limited’s startling contemporary relevance. This was clear in Rachel Gianesse Middle’s revelatory performance of Princess Zara. I had the chance to speak to Middle after the Friday night show and we see this character in a similar way. Zara, oldest daughter of King Paramount, Girton educated, seems sweet with her love of the wonderfully named Captain Arthur Fitzbattleaxe, but she is a zealous reformer, even a proto-fascist determined to take as much control of Utopia as she can through the Flowers of Progress who are there to turn Utopia into a new England.

Zara is the ruthless colonialist who wants to take over her people with missionary fervor and, under the cover of more powerful men like the Flowers and her father, bring to Utopia the capitalist inequities England is still known for. Middle’s beautiful voice and plastic, expressive face indicate Zara’s nature at every turn: in one song she will sometimes look lovely, sweet and innocent in her red dress and pearls, but in the next line her grin will get excessive and her cult-leader nature will show itself. Remmers, Middle and Roselle show us the harm that comes to cultures modeled “on the English scheme,” as today, many postcolonial societies are still trying to extricate themselves from English, French and Spanish imperial power.

Utopia Opera further expressed the show’s contemporary relevance with some very clever and humorous use of the supertitles screen, all planned by Middle, during the famous Act 2 septet, “Society has quite forsaken all her wicked courses.” This minstrel performance usually has the actors playing tambourine; I think it was smart that they took out this unnecessary prop to focus on more on the content of the satire. When the chorus makes obviously ridiculous, delusional assertions of England’s perfection — for instance, “divorce is nearly obsolete in England!” — the screen would show contemporary evidence to the contrary with Guardian articles and statistics. There are some wonderful contemporary zingers here. For instance, when the group sings about England’s theatrical propriety, on the screen appears an article about Magic Mike making its way to the UK! Even better, when the song refers to England’s literary merit, the screen shows disgraced, transphobic Harry Potter writer, JK Rowling, burning up in flames! As someone deeply committed to LGBTQIA+ rights, and the proud, loving wife of a trans woman, I thoroughly appreciate this joke!

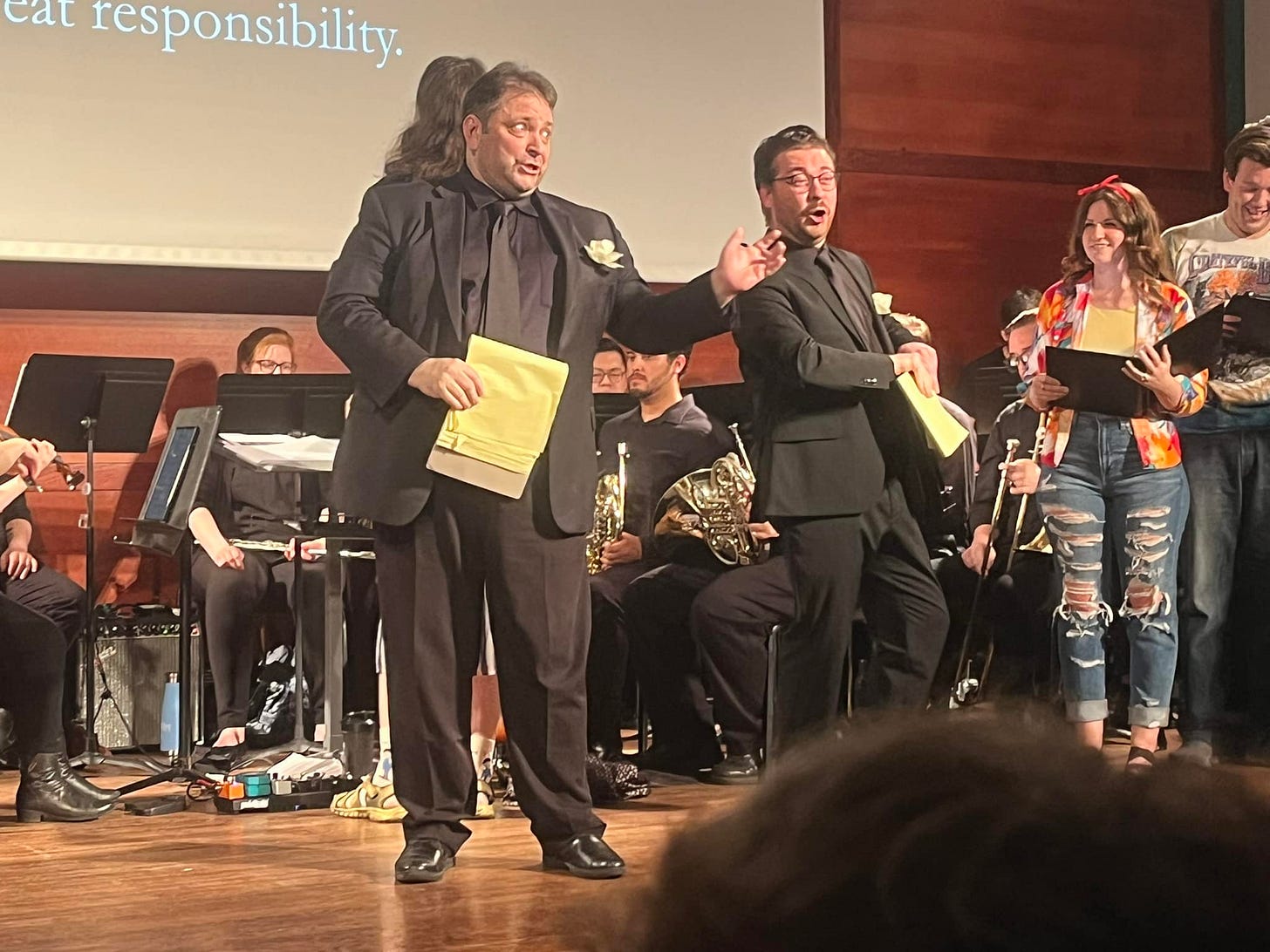

The show had an excellent balance of biting satire, as I discussed above, and plain-old comedic fun, which was put on display through the hilarious team of Vincent Gover and Ben Spierman who played Wise Men Scaphio and Phantis respectively. (I got to sit next to Spierman’s mom, Helene, at the Sunday show — not only was she delightful, she performed in Utopia as a teenager and knew the show inside and out! She wasn’t as enthusiastic about the fast tempi as I was, but that’s ok. When there was a mistake, she’d say “oy.” I love my fellow Jews.)

Gover in particular was full of wild facial expressions, gesticulations and poses, sending the audience into hysterics at both performances. His convulsions over Princess Zara were beyond hilarious. I think Gover is one of the best comic baritones working today. Spierman was also very funny, shouting at Gover that Zara cannot be his ideal woman because Scaphio envisioned a transparent being and she “is opaque!” They are also both accomplished singers and played off each other well.

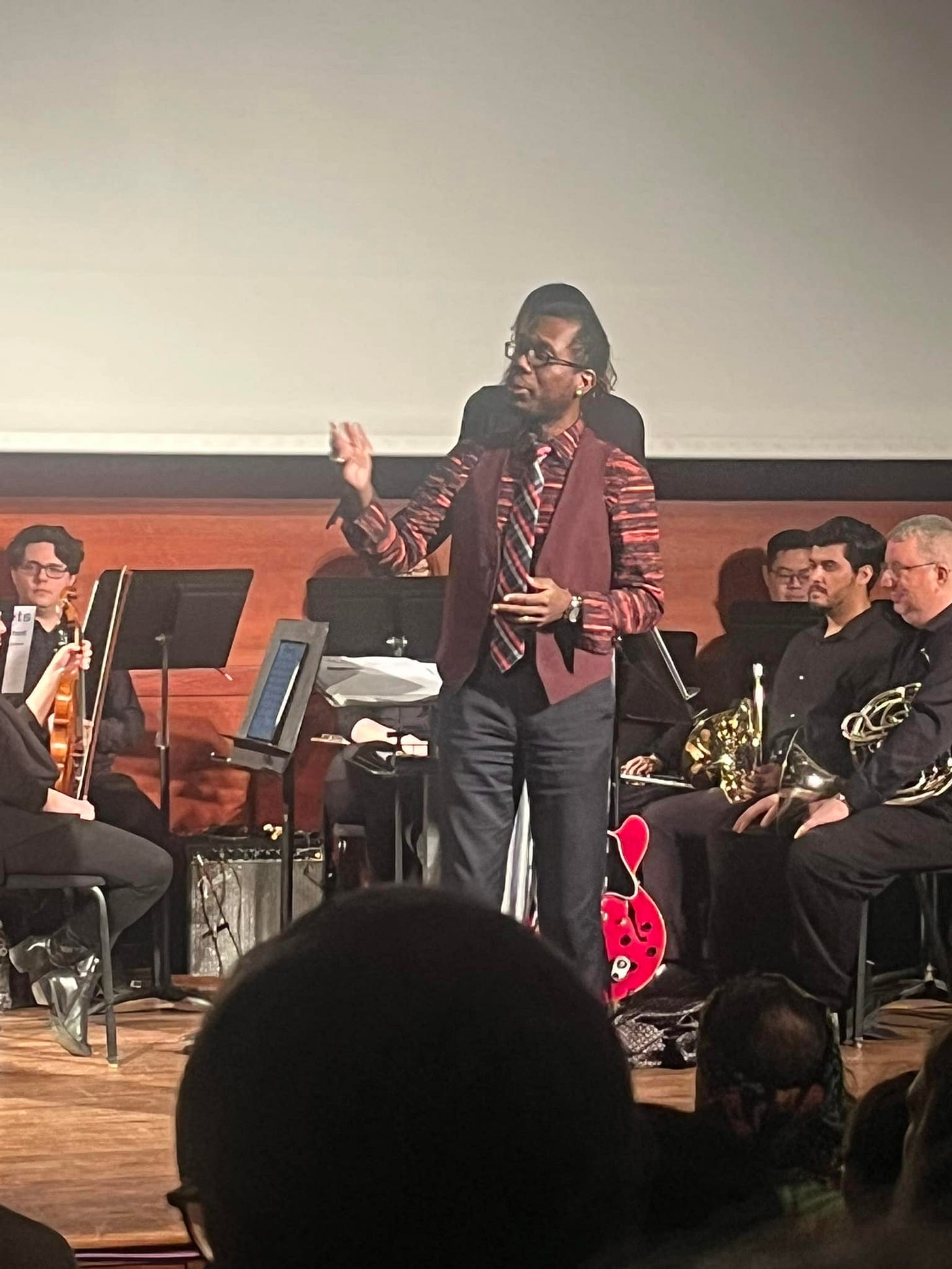

Johari Frasier Menelik’s animated Tarara, the Public Exploder, added to the fun. When it came to Tarara, the company, probably Remmers, made another smart decision: they cut the lines where this character speaks in native Utopian or Gilbert-invented gibberish. Such humor, giving a non-Western culture a nonsense language, is too colonial today, and demeans the many non English speaking cultures who suffered under colonial rule; it was right to excise it.

There were so many great performances it is hard to name them all. Each singer did a wonderful job with demanding solos as Flowers of Progress: Jeff Goble as Mr Goldsbury skillfully handled some very demanding lyrics that dissect the dishonesty of capitalist practices to a rollicking tune. As Sir Bailey Barre, Andrew Buck delivers incredibly smug facial expressions with unparalleled skill. During the famous drawing room scene, he would greet the ladies with appropriate politeness and make faces behind their backs! Henry Horstmann, as Lord Dramaleigh, Alan Smulen as Mr. Blushington, and Rick Agster as call-back Captain Corcoran also embodied their characters with subtle humor and lovely singing. Goble and Horstmann sing a tuneful quartet with King Paramount’s younger twin daughters, played by Vanessa Aldrich (Nekaya) and Stephanie Feigenbaum (Kalyba). A song about English ladies could easily be tedious in 2023 New York City, but the performers carry it off with flair and there’s some good humor in the men winning over the absurdly cold and shy English-style Utopian maidens, who were taught an exceptionally prudish of Englishness by their easily shocked governess, Lady Sophy.

Lady Sophy, the English governess of the twins and King Paramount’s love interest, is often treated as a stock character, someone shrewish, but Casey Keeler plays her better than I knew the role could ever be done. At times her strictness borders on a dominatrix character with her whip/riding crop, corset, and fully buttoned zebra print top. Her “easily shocked” quality makes her a great send-up of English prudishness. But Keeler brings so much more to this character with her rich contralto voice. We see her pride in her charges as the twins act out the “carefully rehearsed emotions” of English ladies. We see her pose with over-the-top drama in her “dance of repudiation” for King Paramount, which is repeated three times, and it is funnier each time. But we also see her let down her guard in an aria about her life and by the end she is giddily in love with the Utopian king, much to his daughter’s horror as she sees Lady Sophy playfully whip her father!

She acts so well with Remmers who not only directed teh show but conducts it and plays King Paramount, often doing conducting, acting and singing at the same time. In fact, when the king finally wins Lady Sophy’s heart, he lets her conduct the orchestra herself, which she does delightedly! I catch myself smiling as I write about the charming and clever ways that Remmers referred to his conducting throughout the performance. For instance, Phantis makes fun of the king’s odd habits and makes conducting motions. At another moment, Scaphio tries to start a coup and starts conducting himself! Remmers’ performance as Paramount, who is a bit clueless but proud of his satirical writing against himself for The Palace Peeper, is as accomplished and humorous as his direction. He, like Rachel Middle who runs Forbear! Theatre in London, is an important force in bringing Gilbert and Sullivan to the modern world. They do so with creativity and, yes, even reverence for what Gilbert and Sullivan wrote. Remmers’ and Middle’s deep love and understanding for G&S shine through everywhere and this is what I value the most.

Overall, the show was an enormous success, making an unwieldy opera entertaining, even breezy, and emphasizing the depth and relevance of its satire. In Utopia, Limited Gilbert skewers English manners as well as colonialism, imperialism, and capitalist corruption in which each nation and each person can become a “limited company.” This is so prescient for the late stage capitalism we are in now. The show balances the harshness of the satire with the goofiness of the humor and the catchiness and beauty of Sullivan’s score. It takes many liberties, but I feel that in the end the show is faithful to Utopia’s lyrics, music, tone and tenor. I’m so glad I went twice.